lupus nephritis

- related: Nephrology

- tags: #nephrology

Lupus Nephritis

See MKSAP 18 Rheumatology for more information on systemic lupus erythematosus.

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

Kidney involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), generally termed lupus nephritis (LN), is a major contributor to SLE-associated morbidity and mortality. Up to 50% of patients with SLE will have clinically evident kidney disease at presentation; during follow-up, kidney involvement occurs in up to 75% of patients. LN has been shown to affect clinical outcomes in SLE both directly via target organ damage and indirectly through complications of therapy.

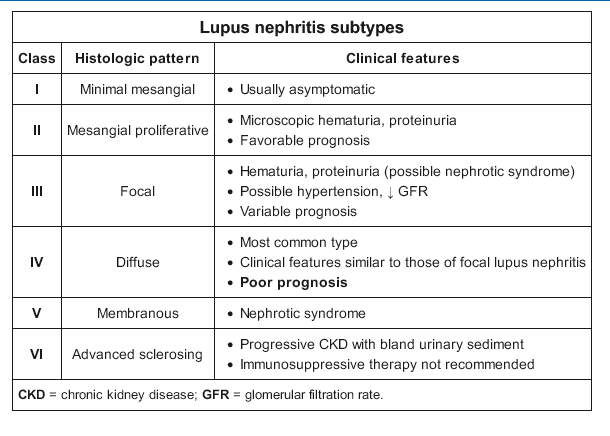

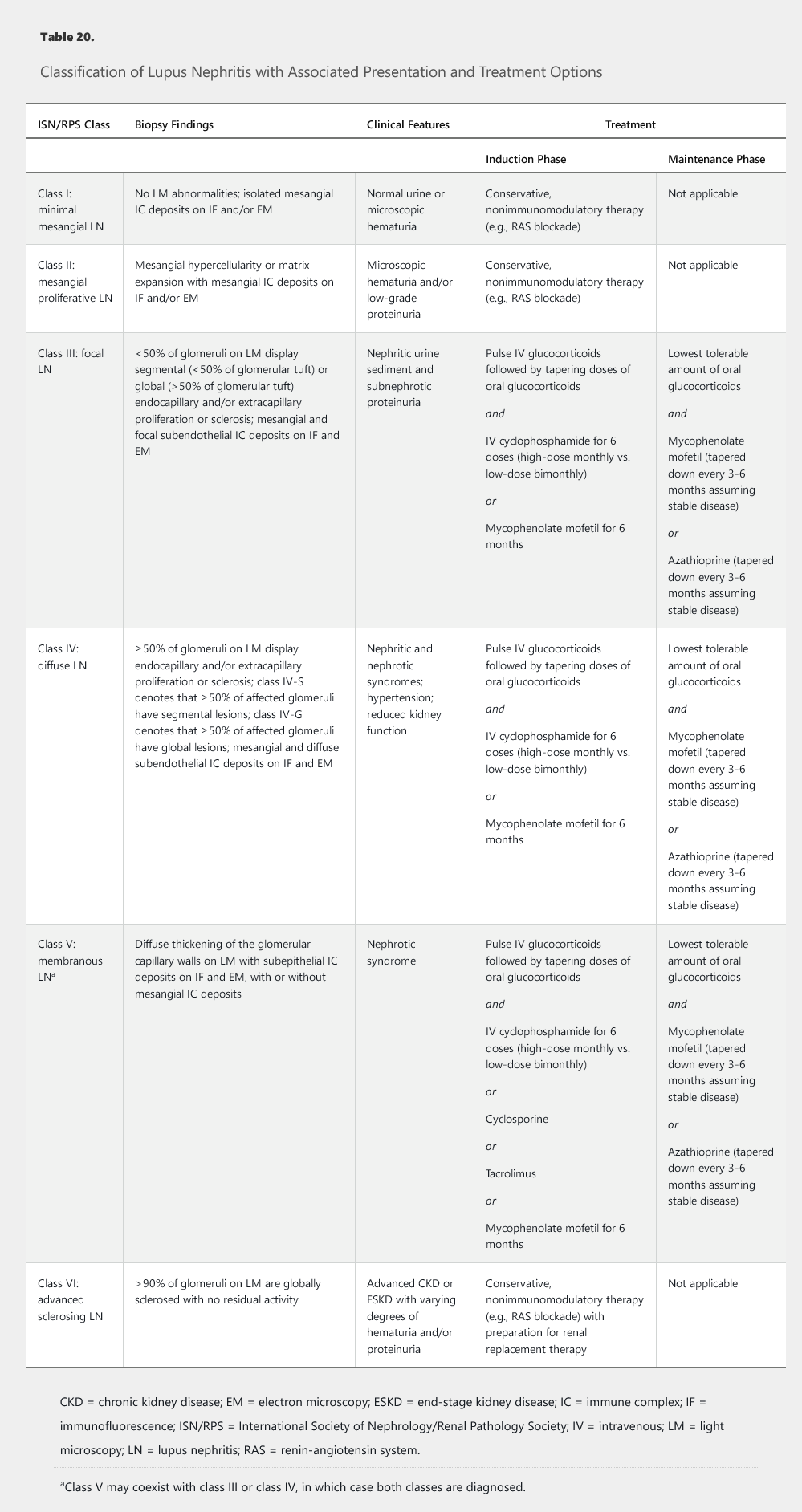

The immune deposits that incite LN are primarily complexes of anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies directed against nucleosomal antigens. A smaller fraction of autoantibodies can also bind directly to chromatin in the glomerular basement membrane (GBM) and mesangium. These immune complexes, when deposited in the mesangium and subendothelial space, are proximal to the GBM and are in communication with the systemic circulation. Subsequent activation of the classical complement pathway, triggered by the DNA/anti-DNA antibody complex formation, generates the potent chemoattractants, C3a and C5a, which elicit an influx of neutrophils and mononuclear cells. The pattern on light microscopy is a proliferative glomerulonephritis that can be mesangial (class II), focal endocapillary (class III), or diffuse endocapillary (class IV) (Table 20). Endocapillary proliferation refers to an increased number of inflammatory cells within glomerular capillary lumina, causing luminal narrowing or obliteration. Immune complex deposits in the subepithelial space can also activate complement but only locally; C3a and C5a are separated from the circulation by the GBM, and hence no influx of inflammatory cells occurs into this space. The injury in this class V LN (membranous) is limited to the glomerular epithelial cells, the primary clinical manifestation is proteinuria, and the histologic pattern on light microscopy is similar to primary membranous nephropathy.

Clinical Manifestations

Typically, patients with SLE initially present with evidence of non–kidney organ involvement (malar rash, arthritis, oral ulcers). After a diagnosis of SLE is confirmed, evidence of kidney disease, if present, usually emerges within the first 3 years of diagnosis. Kidney involvement in SLE first manifests with proteinuria and/or microscopic hematuria on urinalysis; this eventually progresses to reduction in kidney function. Early in the course of disease, it is unusual for patients to present with decreased kidney function, except for very aggressive cases of LN that present as RPGN. The symptoms of kidney involvement tend to correlate with laboratory abnormalities. For example, patients with nephrotic-range proteinuria can present with edema. When kidney function is impaired, elevated blood pressure is a common clinical finding.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of LN is suspected by changes in laboratory parameters (elevated serum creatinine, hematuria and/or proteinuria, low serum complements) but can only be made definitively by kidney biopsy. The classic pattern of LN is an immune complex–mediated glomerulonephritis with a varied pathology that includes six distinct classes of disease (see Table 20). On immunofluorescence microscopy, the glomerular deposits in LN stain dominantly for IgG with co-deposits of IgA, IgM, C3, and C1q in a “full house” pattern. On electron microscopy, tubuloreticular inclusions, which represent “interferon footprints” in the glomerular endothelial cell cytoplasm, are essentially pathognomonic for LN.

Treatment and Prognosis

The current approach to treating LN is guided by histologic findings with appropriate consideration of presenting clinical parameters and the degree of kidney function impairment (see Table 20). Important recent changes in the management of LN include the preferential use of mycophenolate mofetil over cyclophosphamide as induction therapy for LN classes III, IV, and V based on similar efficacy rates and a more favorable side-effect profile with mycophenolate mofetil (in particular, the non-impact on fertility of mycophenolate mofetil compared with cyclophosphamide in a young patient population with childbearing potential). The landmark ALMS trial showed only a 56% response rate in the mycophenolate arm (compared with a 53% response rate in the cyclophosphamide arm).

Up to 30% of patients with LN will progress to ESKD within 10 years of diagnosis, depending in large part on the response to the initial course of immunosuppression. Severity of disease at the time of diagnosis as well as Black race, Hispanic ethnicity, and socioeconomic status have also been reported to influence outcomes in LN.